Wide-ranging claims about 'universities for all' are causing harm to students and taxpayers

In the UK, the number of university students has surged dramatically, growing from a mere 3% in the 1950s to around 50% today. This surge has not gone unnoticed, with concerns about the value and cost of a university education increasingly being raised.

Critics argue that the push for higher university participation could further flood the market and divert young people from other, potentially more rewarding, routes. The Taxpayers' Alliance, for instance, has identified 401 "non-courses" in 2007, costing taxpayers over £40m annually. These institutions often include private, for-profit colleges and university branches offering vocational or less rigorous academic programs heavily reliant on government loans and subsidies.

Employers, too, have been criticised for treating a degree as a screening device, rather than evidence of specialist skill. In fact, only about 19% of graduate job advertisements now specify a degree subject as an actual requirement. This suggests that many employers value the broader skills gained during a university education, rather than the specific knowledge of a particular subject.

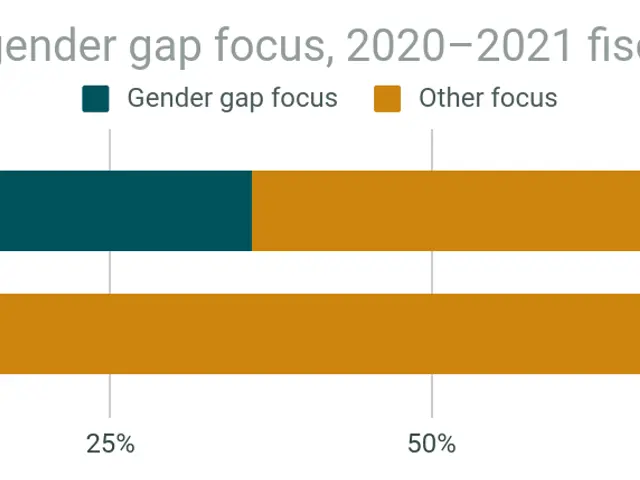

The Institute for Fiscal Studies' figures for lifetime earnings of graduates are based on graduates from the mid-2000s, not today's 50% participation rate. However, these figures show that the graduate premium, or the additional earnings a graduate can expect over a non-graduate, is fading. The average premium for graduates aged 21-30 has fallen from 35% in 2007 to just 21% today, and across the working-age population, the average premium for graduates has dropped from 50% to 36%.

This decline in the graduate premium has led to concerns about the long-term financial viability of the current system. For many school-leavers, starting work at 18 with on-the-job training could deliver better career outcomes than three years accumulating debt for credentials that lack market value. In fact, among those who went to university in the mid-2000s, approximately one in five will earn less over their lifetime, after tax and loan repayments, than if they'd skipped university altogether.

The costs of the current system are significant, with taxpayers shouldering course subsidies and loan write-offs when graduates cannot repay. The Taxpayers' Alliance's chief executive, John O'Connell, states that the current system represents a significant policy failure.

The current system also distorts the labor market, with employers potentially overlooking candidates without a degree who may have valuable skills and experiences. The system also leaves young people worse off, with many graduates facing significant debt and uncertain job prospects.

Despite these concerns, Universities UK, an industry group, wants university participation pushed to 70% by 2040. However, with the graduate premium fading, it remains to be seen whether this ambitious target is financially sustainable and whether it will deliver the promised benefits for young people.

It is clear that the UK's university system is in need of reform. A more targeted approach to university education, one that focuses on providing specialist skills and knowledge in high-demand sectors, could help to address the current graduate crisis and ensure that young people are equipped with the skills they need for a successful career.

Read also:

- Peptide YY (PYY): Exploring its Role in Appetite Suppression, Intestinal Health, and Cognitive Links

- Toddler Health: Rotavirus Signs, Origins, and Potential Complications

- Digestive issues and heart discomfort: Root causes and associated health conditions

- House Infernos: Deadly Hazards Surpassing the Flames