New Orleans Rebuilds Starting from the Ground Up

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the city of New Orleans faced a daunting task: rebuilding and rejuvenating a city that had been inundated, leaving 80% of its surface area underwater and nearly all of its 455,000 residents displaced. The rebuilding process was not without controversy, but it was clear that the spirit of the city was not broken.

One of the most contentious suggestions came from the Bring New Orleans Back (BNOB) panel, who proposed prohibiting rebuilding in low-lying neighborhoods unless they could first "prove their viability." This proposal was met with resistance from residents, who felt that it was their right to rebuild their homes and communities.

Despite the challenges, there were those who saw the rebuilding process as an opportunity to create a more resilient city. Tulane University architecture professor Byron Mouton, for example, runs a program called URBANbuild, where students design and build modern, hurricane-resistant, but affordable houses in New Orleans's most run-down neighborhoods. These houses are raised about five feet off the ground and combine elements of an elevated, New Orleans-style cottage with those of a Manhattan-style loft.

Martin Landrieu, an attorney and officer of the Lakeview Civic Improvement Association, echoed Mouton's outlook, emphasizing the importance of schools and churches in the rebuilding process. Father Nguyen The Vien and his parishioners in New Orleans East repaired their church and used it as a base for rebuilding their homes, as well as lobbying for public services.

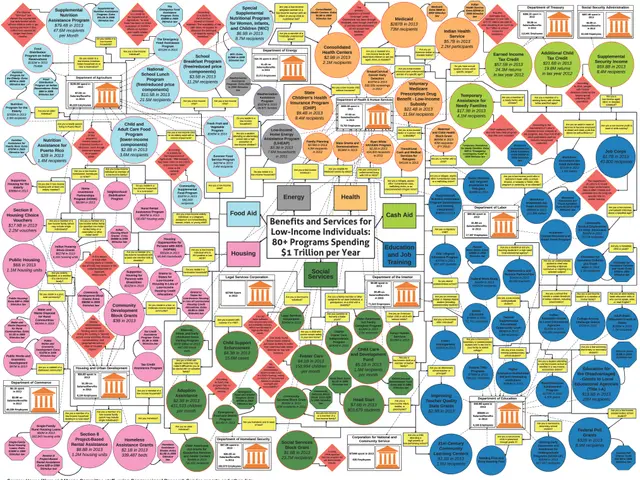

The government played a role in the rebuilding efforts, with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers taking on the task of assessing, repairing, and rebuilding the levee system and flood protection infrastructure. Federal agencies, such as FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers, also cleared debris, unclogged waterways, and provided trailers for residents, and are working on upgrading flood-control infrastructure.

Actor Brad Pitt's team, Make It Right, also contributed to the rebuilding efforts, planning to build 150 houses for property owners whose homes were utterly destroyed in a hard-hit Lower Ninth Ward tract. The houses were designed to be elevated, mold-resistant, flood-resilient, energy-efficient, and meet strict wind-speed codes.

Despite the help from organizations like Make It Right, many New Orleanians chose to rebuild on their own or with small-scale help, rather than under top-down decree. This showed that thousands of individual planners are better than one master, as the city began to take on a unique and diverse character.

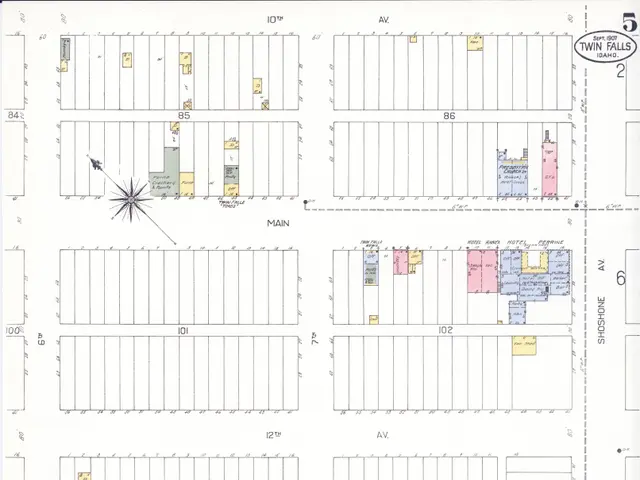

By early 2008, Father Vien reported that 95% of his parishioners were home and the trailers were gone. As of January 2008, New Orleans had 302,000 residents, with 2,000 more returning each month. Habitat for Humanity has launched and executed one of New Orleans's most ambitious post-Katrina building projects, conjuring up a whole neighborhood on five square blocks of the Upper Ninth Ward.

The government's single most important task, however, was protecting citizens from violent crime in a city that was dangerous before Katrina and is more so now. Architect Daniel Libeskind compared New Orleans to postwar Berlin and suggested a "theme" of jazz for a rebuilt New Orleans. The Habitat homes fit neatly into their surroundings and are "consistent with the culture," as Habitat New Orleans's executive director Jim Pate says.

In the end, the rebuilding of New Orleans was a community-led effort, with residents, organizations, and the government working together to create a city that is more resilient, diverse, and vibrant than ever before.

Read also:

- Peptide YY (PYY): Exploring its Role in Appetite Suppression, Intestinal Health, and Cognitive Links

- Toddler Health: Rotavirus Signs, Origins, and Potential Complications

- Digestive issues and heart discomfort: Root causes and associated health conditions

- House Infernos: Deadly Hazards Surpassing the Flames